-

Middle East Policy has been one of the world’s most cited publications on the region since its inception in 1982, and our Breaking Analysis series makes high-quality, diverse analysis available to a broader audience.

-

Middle East Policy has been one of the world’s most cited publications on the region since its inception in 1982, and our Breaking Analysis series makes high-quality, diverse analysis available to a broader audience.

By Shannon Beacom and Medlir Mema

Fellows at the Middle East Policy Council and co-hosts of MEPC’s The BlindSpot.

Executive summary

On April 6 in Vienna, the United States and Iran began to engage in indirect talks on the possibility of rejoining the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or the Iran nuclear deal). The talks signal a promising shift back to diplomacy and an opportunity for the Biden foreign-policy team to set itself apart from previous administrations. In this issue, we provide a brief introduction to the JCPOA, explain how the deal unraveled, and analyze why it remains relevant in light of recent developments in the region. Finally, we highlight important, albeit at times neglected, aspects of the negotiations that require greater attention by U.S. lawmakers and the policy community.

To learn more about the JCPOA, the Vienna talks, and the future of U.S.-Iran relations, check out the latest episode of MEPC’s The BlindSpot featuring an interview with Trita Parsi, the executive vice president at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and an award-winning author and leading expert on Iran.

What is the JCPOA?

The JCPOA is a landmark agreement meant to curb Tehran’s growing atomic program. Signed by Iran, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Russia, and China in 2015. The deal was criticized by U.S. Middle East partners, including Gulf Arab countries and Israel, who expressed concern that they were neither consulted nor included in the negotiations. These states continue to oppose the agreement. The deal targets critical aspects of Iran’s nuclear program in order to limit its nuclear capabilities, and reduce to at least one year the time it would take for Iran to acquire a nuclear weapon (the country’s “ break-out time”).

There are three main critiques of the JCPOA. First, under the agreement, Iran retained its ability to conduct research and development on centrifuges. Second, the deal gave Tehran relief from sanction that were originally aimed at its missile program, regional activities, and nuclear progress. The JCPOA only addressed the atomic program, ignoring the other two areas of concern. Finally, some components of the deal had sunset clauses of between six to 13 years, making it far from a permanent solution.

In 2018, President Donald Trump announced U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and the reinstatement of secondary sanctions on Iran, and additional sanctions as part of a “maximum pressure” approach. The goal was to force Tehran back to the negotiating table to address the United States’ and regional allies’ concerns with the JCPOA. In the meantime, the other signatories have attempted to keep the deal afloat, encouraging the United States to rejoin.

Why is the JCPOA important now?

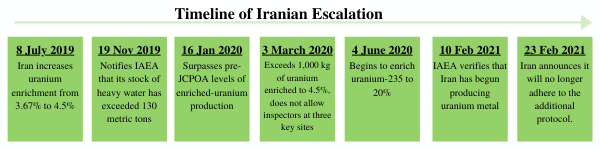

In the spring of 2019, following U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, Iran began to unilaterally reduce its compliance with key requirements. These breaches have brought Tehran closer to obtaining a nuclear weapon than when it signed the accord in 2015. Furthermore, the Islamic Republic shows little interest in compliance until the United States provides sanctions relief, as was promised under terms of the agreement. On the other hand, Washington has insisted that it will not rejoin the deal until Iran returns to full compliance.

*Information from Arms Control Association, 2021

The future of the JCPOA has also become an important campaign issue in Iran, where the voters will go to the polls on June 18 in the country’s presidential elections. With conservative candidates favored to win the elections, it is likely that any future negotiations between Washington and Tehran will become more complex. It is improbable that Iran will agree to put its missile program or regional activities on the table. Even more noteworthy is the fact that some of the critical restrictions on the nuclear program are due to expire over the next year or two. As a result, it is necessary for the United States and its Western allies to settle on either an extension of the JCPOA or a new framework to contain the nuclear program.

To further complicate discussions, the opinions of other signatories vary on what Washington should do. European partners want the U.S. to return to the deal, leaving further restrictions to be negotiated separately. Furthermore, there is potential for the European role to expand as some have suggested that the European Union could be the ideal candidate to coordinate a resumption of the JCPOA. Not only could the Union oversee the compliance of both nations, but, as some in Iran believe, conservative European politicians might convince U.S. Republicans to get on board.

Russia and China also want to keep Iran’s nuclear program contained, even as both countries’ relations with Tehran have expanded in the last few years. Iran works with Russia in the Syrian civil war, and in March 2021 chose to extend a cooperation treaty with Moscow, originally signed in 2001. Additionally, a UN arms embargo that prevented China and Russia from exporting arms to the Islamic Republic expired in October 2020, opening the door to greater military cooperation.

Importantly, Iran recently signed a deal with China to export oil in exchange for significant investments in the economy, including in infrastructure, oil, gas and petrochemicals. The exact amount of the promised investment is unknown as there are no hard numbers or promises in the agreement. However, estimates have placed it between $400 to $600 billion, which many see as an attempt by Iran to diversify its economic and security ties in the face of ongoing U.S. sanctions.

In the Middle East, U.S. allies’ opinions range from staunch opposition to wary acceptance of some sort of deal. Israel is the most vehemently opposed and, in January 2021, threatened to take military action against Iran if the United States rejoined the JCPOA. American partners in the Gulf are taking a different approach by stating their desire to be a part of negotiations to address Tehran’s regional activities and missile programs. The Abraham Accords also represent a continued effort by Israel and Arab countries, specifically Saudi Arabia and the UAE, to keep the Islamic Republic regionally isolated. The normalization of Israeli-Arab relations signals a shift in perception of the greatest threat in the region, from Israel to Iran.

Not only does Israel oppose the deal and any return to it, over the last three years, it has also conducted a “shadow war” against Iran. In April of 2019 Israel attacked Iranian oil tankers and commercial ships in the Red Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, thus opening a maritime front in their campaign to destabilize Iran. Other accidents occurred in 2020, including a gas-tank blast near the Parchin military complex in July and a bomb explosion at the Natanz facility merely six days later.

In November 2020, Iranian scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, considered the father of Iran’s nuclear program, was assassinated outside of Tehran. Iran responds to Israeli attacks through a variety of means, usually clandestinely, but also sometimes overtly such as hitting an Israeli cargo vessel in the Arabian Sea in March 2021. In April 2021, two suspected Israeli attacks occurred. The first was an Iranian cargo ship hitting a suspected Israeli mine in the Red Sea. The second attack occurred on April 11th, when the Natanz facility had a power failure from a suspected Mossad sabotage attempt. Several thousand centrifuges were damaged or destroyed.

What are we missing?

The return to the negotiating table presents a rare opportunity for advancing a diplomatic solution in a region continuously rocked by instability and violence. However, given the various competing interests and differences between the United States and Iran, as well as overt opposition by domestic actors and allies in the Middle East, it is clear that the road forward remains as challenging as ever, or perhaps even more so. As a result, it is important for the Biden Administration to engage in current and subsequent talks fully aware of important developments since 2015 that are likely to affect the attitudes of actors in the region and at home.

First, while some suggest that, given the lack of specificity and hard commitments, the China-Iran deal changes very little in the short term. However, its timing gives Tehran some leverage and confidence in the ongoing Vienna discussions and may even embolden hardliners to spurn U.S. concessions offered in return for full compliance with the JCPOA.

Second, the Abraham Accords, which emerged in the aftermath of the fallout of the nuclear deal, promise to reorient regional priorities and alliances, including on the issue of Palestine. In a bid for relevance, the Palestinian Authority announced that parliamentary elections will be held in the summer of this year. Along with elections in Syria and Iran, and post-election drama in Israel and Lebanon, the competition for attention and resources is only likely to increase, as is perhaps regional instability. Given the transactional nature of the accords and their thin institutional foundation, it is not yet known how durable relationships are between some of the Gulf countries and Israel and whether they can thrive in the current atmosphere.

Third, as some have suggested, for the JCPOA to survive, the U.S. administration should find ways to transform the agreement from a partisan issue, to one that is seen through the prism of national-security-interests. Recent proposals include the possibility of lifting primary sanctions on Iran to secure an ‘economic windfall’ in GOP districts. While this is unlikely to sway committed opponents of the deal, it may ensure bipartisan support for a renegotiated final deal. Additional agreements on Tehran’s missile program or regional activities should be done separately and should include Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and others affected by Iran’s activities.

Finally, it bears emphasizing that one of the most corrosive aspects of the Trump Administration’s legacy is the loss of U.S. credibility in the region and around the world. Allies are willing to give President Joe Biden the benefit of the doubt. However, it is clear that Trump’s actions are not viewed as an anomaly outside of the United States. Allies and rivals alike have become more wary of concluding agreements with Washington, in case subsequent administrations retreat from commitments. Rebuilding trust in the United States must remain a priority for the administration.