An article in Middle East Policy’s Summer 2024 issue examines the history of Turkey’s constitutions as new revisions may be on the horizon.

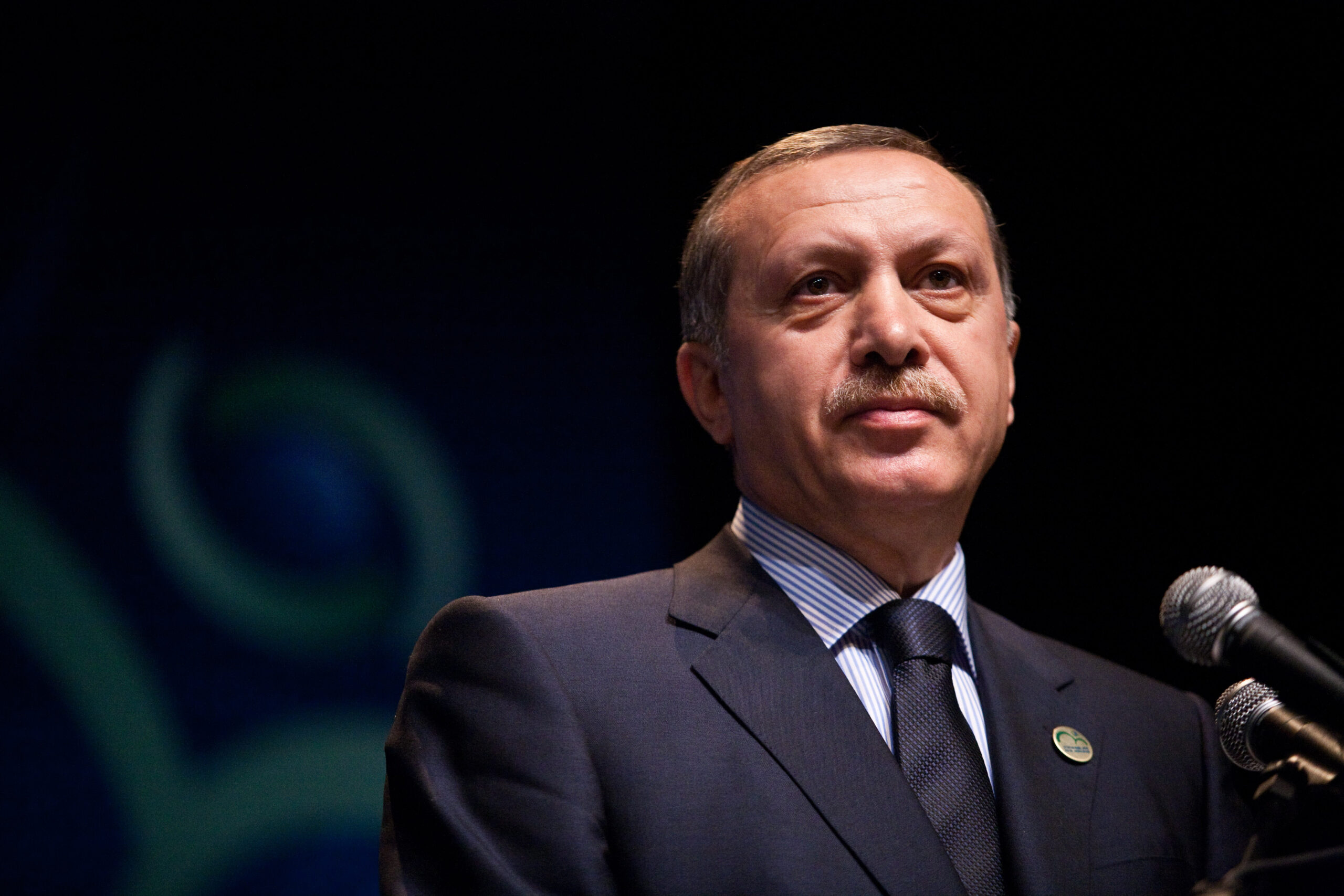

In the past year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has called for a new, civilian-drafted constitution to replace the current document adopted in 1982 by a military junta. In his speech, he asked for political parties, academics, and other experts to help draft the new constitution; at the same time, he criticized other parties and claimed that only his, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), has taken real action.

This is not the first time Erdoğan has made this call. In 2017, a draft constitution was approved by voters in a nationwide referendum; despite this victory in the public sphere, members of the government were far less enthusiastic. For many, it seemed that the proposal would shift Turkey from a parliamentary to a presidential republic.

The suggested changes led to a consolidation of power: the president now heads the executive and serves as head of state while maintaining party ties, and the position’s powers have expanded significantly, undermining the system of checks and balances. Parliament can be dissolved, the judiciary manipulated, and members of parliament can no longer scrutinize ministers. The opposition claimed that the document would “entrench dictatorship”; notable given the clause that allowed for a third presidential term, which Erdoğan won in 2023.

Despite the concerns over the 2017 changes and the recent push to replace the existing constitution, Ayşe Y. Evrensel explains in a new Middle East Policy article that undemocratic constitutional reform is not a new phenomenon in Turkey; indeed, “constitution making has been authoritarian in nature” over the last 180 years. She compares the processes from the Ottoman period up to the modern day, splitting reform movements into four eras.

In the first era, Ottoman leaders were pushed by foreign powers to create a constitution they had no interest in. Reforms up until the early 20th century were largely unsuccessful in reducing the sultan’s power. A second era emerged with the growth of groups like the Young Turks, which focused on Western political ideals, and the collapse of the empire following its defeat in World War I. The creation of and revisions to a new constitution in 1921 and 1923 reflected the interests of these groups in the new Republic of Turkey, even as most of society was not consulted.

Following a military coup, the third era begun with a new constitution in 1961; major revisions in 1971 and 1973 were then replaced with yet another document in 1982 by the ruling military junta to address an increasingly fractured and unstable society. In doing so, power was centralized; Evrensel notes that “some argue the 1982 constitution was designed to protect the state from its citizens.”

The scholar argues that the state is now in its fourth era of constitution making, and it might be the most undemocratic yet. Revisions since the 2000s—including the aforementioned 2017 referendum— have further consolidated power in the executive, and because of Erdoğan’s close connection to his party, the AKP itself.

This modern era began with some hope of change; as the AKP rose to power, reforms pushed for European Union (EU) integration, expansion of civil rights, the abolition of the death penalty, and a reduced role for the military. But the EU agenda was dropped in the mid-2000s after some European opposition, and the country took a turn towards authoritarianism.

The government launched investigations into opposition party members, viewed as attempts to neutralize opposition. Efforts were made for constitutional reform up until the implementation of the 2017 referendum, when the AKP saw their work come to fruition by riding heightened security concerns after a coup attempt in 2016. Since then, critics argue, “the rule of law has been systematically ignored.”

Evrensel ultimately narrows down the focus to one pervasive failure in Turkish constitution making: extreme shortsightedness. All reforms have been aimed at solving perceived emergencies, but have no long-term view or any broad-based negotiation to seek consensus and are often “changed only due to shifts in the identities of the key elites.”

As Erdoğan pushes for yet another constitution, the future is uncertain. Past efforts have shown how the processes have led to “a decline in democracy,” driven by incumbents’ “fear of losing power.” With a narrow presidential win in 2023 and widespread losses in this year’s municipal elections worrying Erdoğan and the AKP, Evrensel concludes, “it is not clear where future revisions would lead.”

Among the major takeaways readers can find in Ayşe Y. Evrensel’s Middle East Policy article, “Constitution Making and Enduring Challenges to Democracy in Turkey”:

- Erdoğan’s narrow victory in 2023 will likely lead to constitutional revisions that shore up the power of the ruling AKP.

- Constitution making and revision in Turkey has historically been authoritarian in nature.

- The most common characteristic is the absence of a long-term view or broad-based discourse.

- The process being urgent and short-term has encouraged a top-down elitist approach that lacks legitimacy.

- The first attempts at constitutions occurred under the Ottoman Empire and were unwillingly accepted by the sultan. Pressure from Europe and the Young Turks maintained the constitution but failed to reduce the sultan’s power.

- The second constitution in 1921 provided excess power to the elites that created authoritarian outcomes, even in a state that was technically democratic.

- Reforms between 1961 and 1982 demonstrated high public support for authoritarianism. Revisions focused on tackling perceived threats to the Turkish Republic led to increased polarization.

- The 1961 and 1982 constitutions received strong public support, though their primary outcomes were the strengthening of the military and executive.

- Parties and leaders engaged in fierce competition and often failed with communication and compromise.

- Because of continued conflict between mainstream parties, an alternative group of Islamists began to rise.

- Two key members, Abdullah Gül and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, formed the Justice and Development Party that maintains a strong hold today.

- The rise of the AKP and its governance and reforms were welcomed by the west, though the EU expressed concerns about significant democratic restrictions.

- Between 2001 and 2004, a constitution was formed to reflect EU values, and reforms allowed Erdoğan to run for president despite a prior criminal conviction.

- Continued criticism forced the AKP to drop EU membership from its agenda, but the bid had already established Erdoğan’s status.

- In the late 2000s, reforms consolidated Erdoğan’s leadership and continued efforts made clear that future revisions would seek to increase the power of the executive.

- Following an attempted coup in 2016, Turkish citizens voted for a referendum that all but eliminated the parliamentary system in favor of an even stronger presidency.

- Three key points stand out regarding the challenges of Turkish democracy:

- Constitution making has emphasized problem solving over principles, encouraging a top down, elite-driven process.

- Constitutions have served as reflections of Turkish culture.

- Two periods of constitution making can be identified: between 1960 and 1980, constitutions were the product of multiparty chaos; and revisions from the 1980s onward have served the rise of Islamism.

- Collectivist culture in Turkey promotes group identity over individual rights, which has led to little reform for citizens and an increase in the power of government and parties.

- The primary issue with Turkey’s approach to constitution making has been shortsightedness, which attempts to solve perceived emergencies but not establish a stable state.

You can read “Constitution Making and Enduring Challenges to Democracy in Turkey” by Ayşe Y. Evrensel in the Summer 2024 issue of Middle East Policy.

(Banner image: UNAOC)