A new article analyzes Washington’s policy shift in the region as it evaluates relationships and

faces rising Chinese influence.

When the Israel-Hamas war broke out last October, the world looked to major international players to lead a response. Among them were the United States and China, two countries that wield significant power in the Middle East.

China moved quickly, calling for an immediate ceasefire and humanitarian support. The country’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, asserted strong support for the Palestinians and a two-state solution: “the crux of the matter is that justice has not been done to the Palestinian people… the way to solve the Palestinian issue lies in resuming genuine peace talks as soon as possible and realizing the legitimate rights of the Palestinian nation.”

China has generally been cautious about taking sides in the region and has often looked to position itself as a mediator. Earlier in 2023, Beijing successfully oversaw a normalization deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia, a feat the US was unable to accomplish. The US has also turned to Beijing to utilize its many close economic and political ties in the region, particularly in Iran, to avoid further conflict.

China’s recent success in expanding its influence in the region has forced the US to reevaluate its approach to the Gulf. Rachel Moreland analyzes this shift in policy in a new Middle East Policy article, arguing that, while the two superpowers will still compete, they are also “presented with another opportunity to cooperate in the region.”

In the years since the Obama administration, concerns over the perceived drawing back of American commitment to the Middle East have grown. But Moreland argues that “despite the narrative of US withdrawal from the region, the Gulf remains of strategic importance to American global strategy.” Instead, Washington’s “Middle East policy is recalibrating with respect to China’s growing presence in the region.”

This recalibration has been defined by a reduction of resource investment and reassessment of key strategic partners. As Chinese influence grows, the US has begun working on strengthening those partnerships in the Gulf that aid in deterring Iran. Washington has also been forced to rethink its relations with states over the fault lines of the war in Yemen and human rights abuses, like the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

While the Biden administration has been hesitant to cooperate with major Gulf players like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) because of these concerns, continued Chinese efforts have led to stronger ties with those states.

One major point of contention was the use of Huawei technology, especially in the UAE. Deemed a security risk by US administrations, Washington froze a $23 billion sale of F-35 fighter jets to Abu Dhabi over the concerns. But as the Emirates have become increasingly digitized, the value of Huawei’s large, high-tech 5G infrastructure holds great appeal.

The pushes from both sides means that “Gulf states have been left feeling caught in the middle of a great-power rivalry and struggling to pick a side in the Sino-American ‘digital cold war.’”

Moreland argues that while the “deep American footprint” might be lessening, it does not constitute withdrawal, nor submission to Chinese influence. She argues that “nobody expects China to replace the United States in military terms.” The important roles of each leaves Gulf states hedging their bets, “trying to maintain relations with Washington while engaging more deeply with China, which has positioned itself as a favorable external great-power partner.”

Ultimately, though, there may not have to be a choice made. Moreland notes that Sino-American cooperation could be positive and serve each side’s interests, because “neither party benefits from a Middle East made increasingly unstable.”

The Israel-Hamas war is presenting Washington and Beijing a new opportunity for cooperation to create a more stable future for the region. Still, as the world continues to wait for China to respond in a substantial way and China remains critical of the US failure to promote peace, the future of Sino-American cooperation remains in flux.

Among the major takeaways readers can find in Rachel Moreland’s Middle East Policy article, “Shifting Sands: US Gulf Policy Recalibrates as China’s Regional Ambitions Grow”:

- The narrative that the US is withdrawing from the Gulf is false; Washington is instead recalibrating its policy with respect to China’s growing presence in the region.

- Since the Cold War, the US has operated as the dominant external player in the Gulf.

- The election of Obama in 2008 marked a change toward increased focus on Asia.

- President Biden’s Middle East strategy is largely focused on recalibration, defined by a shift in resource allocation invested and a reassessment of key partnerships.

- A primary priority of US Gulf policy has been the deterrence of Iran.

- Years of inconsistent approach have made this policy less effective, but an increasing willingness to exercise diplomatic tools marks a significant change.

- In March 2023, China brokered a deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia to resume diplomatic talks; meanwhile, the US has been struggling with poor relations with Iran.

- This agreement turned the binary in the Gulf—that the “US does security and China does the economy”—on its head.

- Beijing’s diplomatic success may suggest that China, not the US, has become the greatest external power with leverage over Iran.

- Washington has also begun resetting its relations in the Gulf, particularly regarding defense cooperation.

- The Biden administration has become more hesitant to support powers like Saudi Arabia and the UAE militarily because of their involvement in the war in Yemen and concerns over human rights violations.

- The UAE suspended talks, however, and maintains diverse weapon suppliers, including China.

- Military agreements with China remain underdeveloped in comparison to deals with the US, who continues to maintain a significant military presence in the region.

- The US has also begun combatting Chinese involvement through their “technology containment” policy.

- As the Gulf becomes increasingly digitized, the US is attempting to deter states from utilizing Chinese-owned tech giant Huawei technology in their digital expansion.

- The relative success of the campaign, particularly in Saudi Arabia, indicates that the US still wields considerable influence, but the attraction of China is its offer to Gulf states of greater agency over their choices.

- Washington and Beijing cooperation in the region may lead to greater stability, as the US security umbrella protects Chinese economic interests and Chinese investments promotes stabilization that supports a US military presence.

You can read “Shifting Sands: US Gulf Policy Recalibrates as China’s Regional Ambitions Grow” by Rachel Moreland in the early look at the Spring 2024 issue of Middle East Policy.

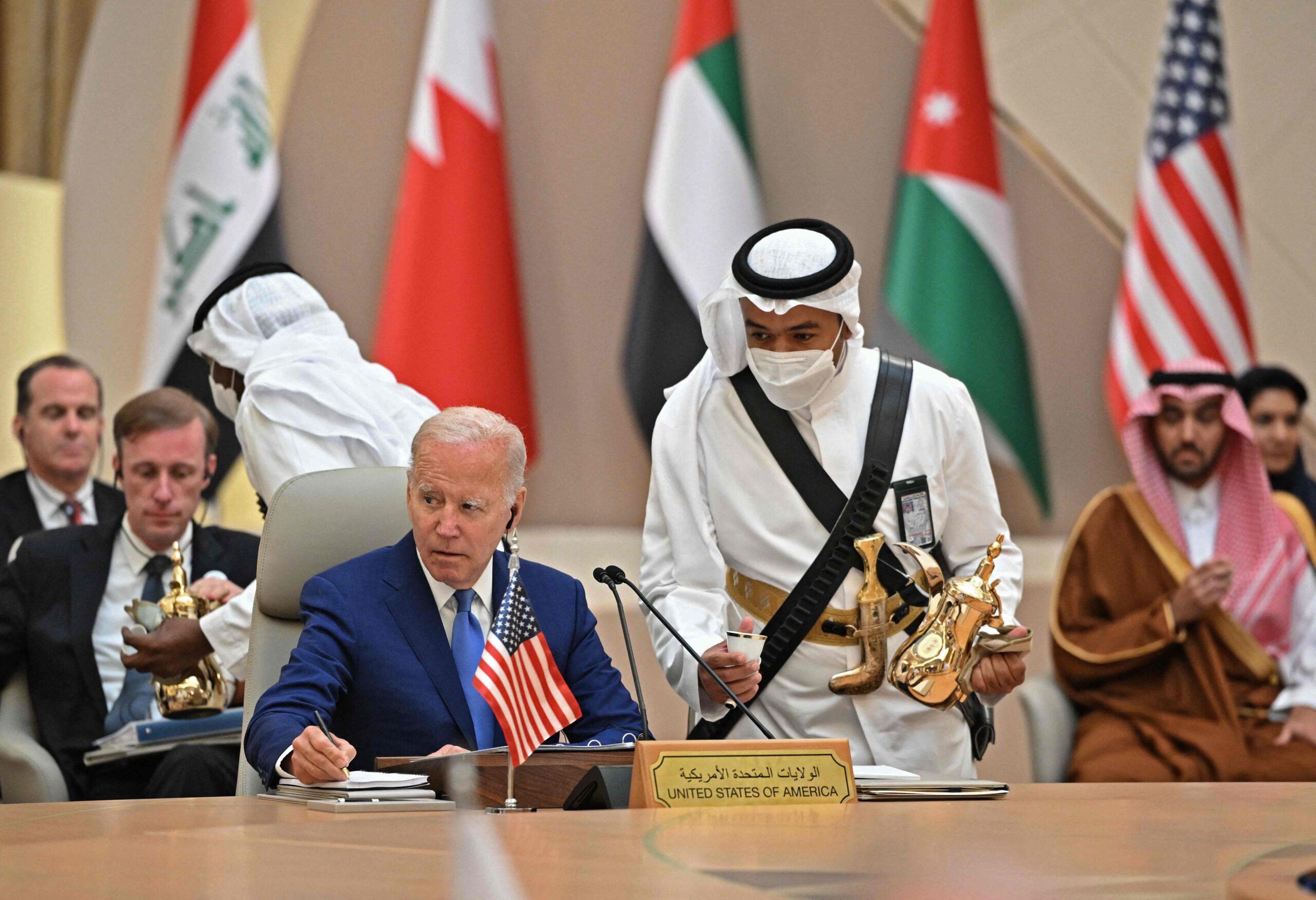

(Banner image: Mandel Ngan)