A new journal article explores how Iraq is battling its internal weaknesses to cooperate with the two superpowers.

Early last month, Iraq and Syria were hit by multiple American airstrikes targeting Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and its proxy forces. The strikes killed nearly forty people and followed a deadly attack by Iranian-backed militias on US troops in January.

The bombings drew mixed reactions. Washington’s European allies, including the UK and Poland, supported Washington’s right to respond; China and Russia, on the other hand, criticized the airstrikes, accusing the US of raising the risk of regional escalation. Chinese Ambassador Zhang Jun proclaimed that “US military actions are undoubtedly stoking new turmoil in this region and further intensifying tensions.”

The remarks exhibit several of Beijing’s increasingly frequent criticisms of US activity in the Middle East. China fears that regional instability would harm their expanding interests in the region and appears to be increasingly focused on stabilization in high-risk states like Iraq. The strikes also provide another opportunity for Beijing to strengthen its image in the region by joining in on anti-Western sentiments in efforts to gain the favor of wary governments.

China’s engagement in Iraq has grown in recent years, most notably in the energy sector. This relationship, and the effects of US foreign policy, are the focus of a new article in Middle East Policy by Amjed Rasheed that argues that, because of Iraq’s complex and compounding foreign and domestic issues, the country is forced to be largely reactive to Sino-American activity and competition, rather than proactive and strategic.

Years of domestic and international conflict have left Iraq’s economy and infrastructure crippled. Beyond the direct financial impacts, the country’s invasion of Kuwait inspired the UN Security Council to create an account at the US Federal Reserve to manage some regime assets, settle claims from the Kuwait war, and utilize oil revenues for development. These revenues, the country’s primary source of income, are routed to the account. With control of this capital outside the state, the financial constraints and stringent sanctions have made Iraq’s economy fragile.

Iraq has continued to welcome the American role of security guarantor. After sovereignty was transferred back to the Iraqi government in 2004, Washington and Baghdad agreed that the US was still a necessary presence in the unstable situation. When the Islamic State came to prominence in 2014, Iraq requested American intervention, which undoubtedly changed the course of the conflict. Rasheed argues that “if the United States were to end its mission and sever diplomatic ties with Baghdad… it could exacerbate internal conflicts, undermine Baghdad’s efforts against violent extremism, and cause economic disruption.”

This close relationship has not entirely prevented Iraq from reaching out to other foreign players, including China. Engagement with China began in 1958, and Rasheed notes that “Sino-Iraqi ties remain rooted in economic cooperation.” The role of Baghdad in the Sino-American competition became visible when war on Iraq was declared in 2003, and Beijing took an opposing stance despite its work to improve relations with the US. In the years since, Iraq has benefited from Chinese investment, primarily under the Belt and Road Initiative, and serves as a critical oil exporter for Beijing.

However, China does not provide a solution for Iraq’s rocky relationship with the US. Iraq is still visibly of low priority for Beijing, with significantly more engagement occurring in other regional states. Additionally, Rasheed indicates that China may see Iraq as less of a partner and more of a security problem that needs to be addressed for their other projects to progress. He argues that “the relationship does not provide Iraq with the power that would allow it to free itself from systemic constraints.”

China is providing critical economic relief to a country that many hesitate to engage economically, but Iraq continues to be hesitant to engage Beijing. Instead, the government has declared that Iraq is seeking to strengthen relations with the US that extent beyond security.

In Rasheed’s assessment, “these efforts aim to harness Iraq’s natural resources, diversify its economic partners, and break free from China’s economic dominance in Iraq.” However, its lack of economic and political power continues to reduce Baghdad’s bargaining capacity, and the country continues to have to respond reactively to the rising Sino-American competition in the region.

Among the major takeaways readers can find in Amjed Rasheed’s Middle East Policy article, “Iraq’s Struggle to Contend With the Sino–US Rivalry”:

- When analyzing Iraq’s foreign policy, it is important to recognize the country as a weak state, a status that forces the government to react passively to systemic constraints.

- One of the key factors that affects Iraqi foreign policy is the state’s financial vulnerability.

- Decades of conflict have left the economy crippled, especially as the state has faced countless rounds of sanctions.

- The US Federal Reserve holds much of Iraq’s oil revenues in the Development Fund for Iraq account created in 2003, managing assets and settling old debt.

- US and Iraq security relations further complicate Iraq’s capacity to make decisions on foreign policy and relationships.

- Following the Iraq War, an eventual agreement was signed in 2011 that recognized Iraq’s sovereignty but required the US to support its security.

- This agreement has helped the US assist the country at Baghdad’s request in modern conflicts, most notably against the Islamic State.

- The ability for this framework to be adjusted when needed makes the US a strong partner for Iraq’s security and acts as a buffer to prevent Iranian influence.

- Alongside their complex relationship with the US, Iraq has important economic ties to China.

- The relationship began in 1958, when Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qasim’s anti-Western rhetoric inspired China to view the country as an entry point to the Middle East.

- In the 1980s, China provided arms in the Iran-Iraq due to concerns over the US and Soviet presence.

- China is Iraq’s biggest trade partner because Beijing is often willing to bypass sanctions to seek oil; China is also one of the only countries willing to invest in Iraq.

- Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait pushed China to dial back engagement, but the relationship has since grown.

- However, China’s engagement with Iraq has been oversold.

- The lack of consistent visits indicates that Beijing still sees Iraq as a weak state.

- China’s engagement with Iraq appears to be primarily based in achieving stability for its larger regional goals, not in providing the state with more economic and political mobility.

- Complex domestic politics have also undermined Iraq’s capacity to organize foreign policy.

- The post-2003 order has created a fractured political system that is increasingly inefficient and corrupt.

- Mixed opinions from domestic parties, groups, quasi-state, and non-state actors reduces Iraq’s capacity to formalize policy and encourages personal, rather than national, goals.

- It is the convergence of these issues that puts Iraq in a position where it can only respond to Sino-American competition, rather than make its own decisions relating to the superpowers.

- In recent years, however, Iraq has signaled a willingness to prioritize relations with Washington.

You can read “Iraq’s Struggle to Contend With the Sino–US Rivalry” by Amjed Rasheed in the Spring 2024 issue of Middle East Policy.

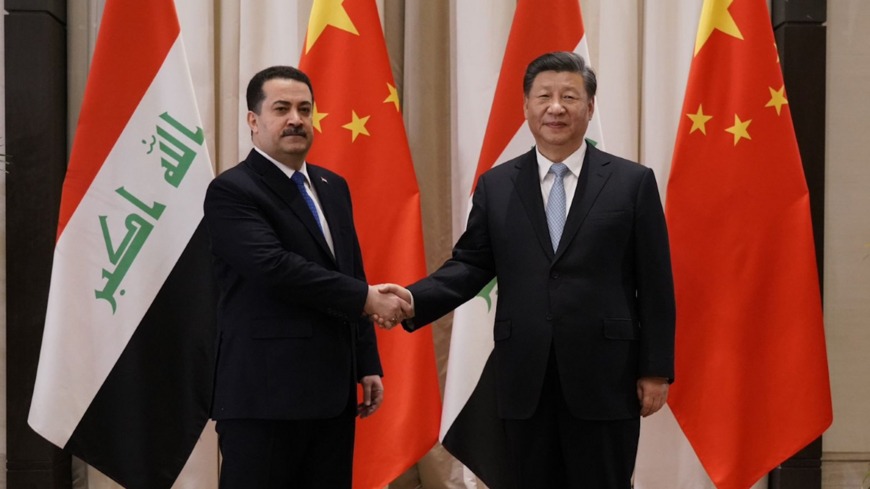

(Banner image: Iraqi Prime Minister’s Office)