A new article analyzes how Maoist thought is influencing Beijing’s foreign policy and relations with Gulf states.

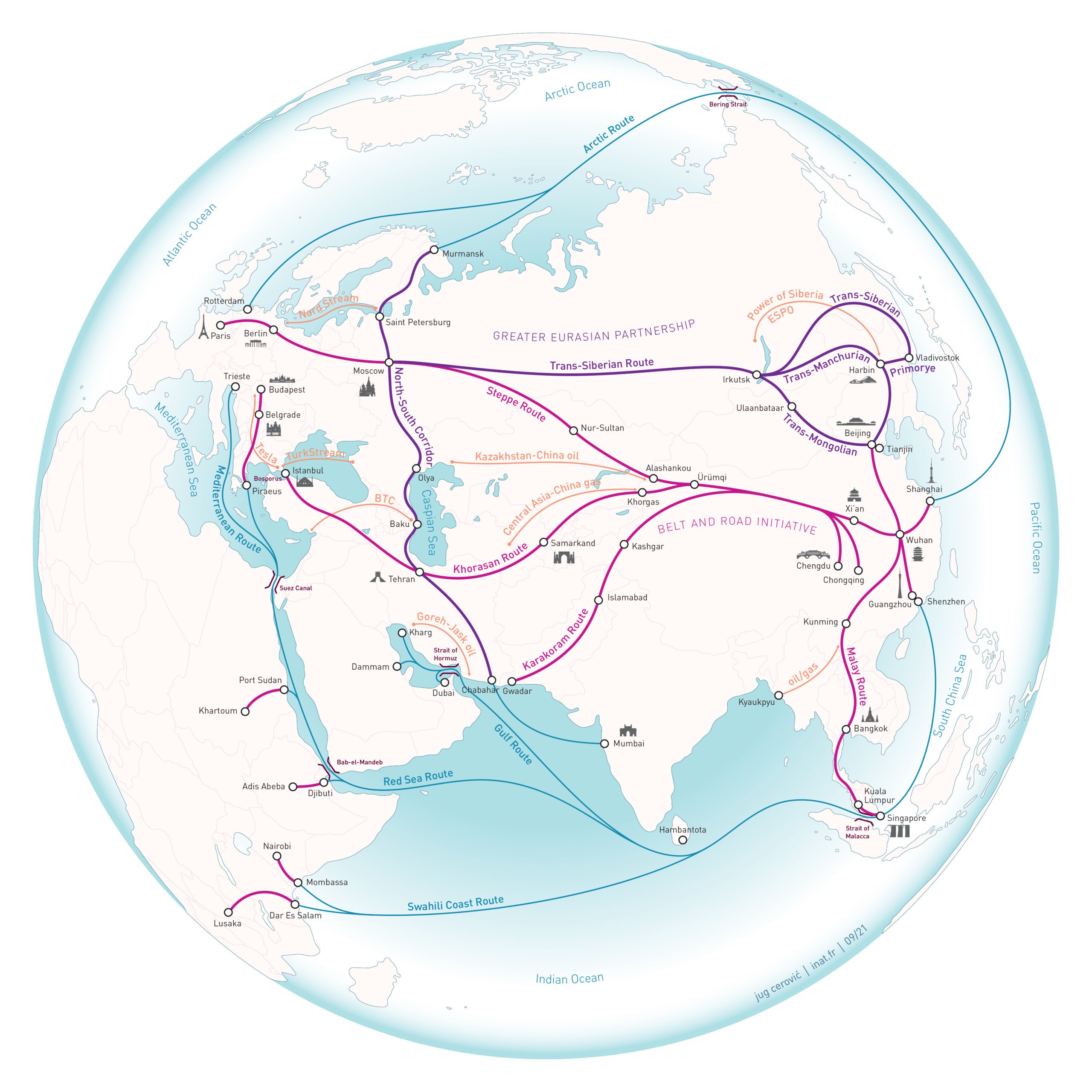

In October 2023, China hosted a summit celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The event was attended by a host of actors from around the globe, including many states who had benefited from the initiative.

The BRI has been a moderate success over the last decade; the Chinese economy has benefited from a major spike in trade, but it has made the country a creditor to hundreds of loans that may not be repaid. Being accused of “debt-trap diplomacy,” more countries involved in the BRI are pulling out from projects for fear of deepening their debt to Beijing.

Despite the many setbacks and mounting issues, it is undeniable that China has succeeded in one of their major goals: extending Beijing’s influence, particularly over the Global South. A senior analyst at Mercator Institute for China Studies noted that “China hasn’t flipped many countries from a Western orientation, but the fact it has moved the needle to a middle ground – that is already a huge diplomatic victory for Beijing.”

A new article published in Middle East Policy supports the belief that this may, in fact, be the goal. Enrico Fardella and Gangzheng She argue that a long history of Maoist-influenced political philosophy has set up China’s contemporary strategy of “soft patronage.” This strategy, they claim, is focused more on combatting American—and historically Soviet—hegemony and does not necessarily intend to replace the United States’ traditional leadership.

The scholars delve into Maoist strategy to understand how it impacts modern Chinese policy in the Middle East. At the center of their analysis is the concept of “intermediate zones,” which under Mao were defined by broad areas, like Africa and Latin America, that were dissatisfied with American and Soviet influence.

By focusing its foreign policy on engagement with these “intermediate zones,” China sought to establish itself as a reliable alternative for countries concerned with Western hegemony. One of the critical pieces of this diplomatic approach was and is vocal support for state sovereignty, a desirable outcome during the Mao regime, but still relevant today as countries are pressured by Washington’s policies. By creating an alternative, Beijing hopes to become central on the global stage and create the conditions for China’s long-term prosperity.

This strategy has been remarkably successful in the Gulf. As China’s energy needs have risen and Gulf powers seek greater diversification, Beijing and regional governments have formed strong partnerships and Chinese investment has continued to rise.

The authors explain that China’s status as a “key economic player that favors the new centrality of the region…has facilitated coordination between Beijing and regional countries. This has in turn reinforced those states’ independence and decreased the space for American hegemonic interference.”

The US has expressed concern with their Gulf allies’ increasing willingness to engage with its rival, but “most Gulf states have no real incentive to sacrifice China ties in exchange for favor with the United States.” China, for its part, has not attempted to challenge America outright in the region, preferring instead to offer alternative opportunities for actors that allow them to slowly detach from Washington.

Beijing’s confidence in strategic diplomacy has visibly grown since the inception of the BRI. Fardella and She conclude that “the dominance of China’s anti-hegemonic strategy has so far prevented Beijing from developing a more independent and assertive regional policy,” but increasing Sino-American conflict many cause China to “attempt to consolidate its influence, [and] may depart from the traditional form of proactive defense…and step into an unprecedented role that combines the newly acquired centrality with traditional forms of dominion.”

Among the major takeaways readers can find in Enrico Fardella and Gangzheng She’s Middle East Policy article, “The Role of the Gulf in the Longue Durée Of China’s Foreign Policy”:

- China’s Maoist-influenced anti-hegemonic strategy has prevented Beijing from being assertive in the Middle East, but the rise of Sino-American rivalry may force them to take more direct action.

- China’s primary long-term goal has been to regain “centrality” in the global arena through efforts to reduce the hegemony of the US and, historically, the Soviet Union.

- Beijing wants to offer an alternative to shape global governance and conditions for China’s own security and prosperity.

- Anti-hegemonic policy has been based on creating a united front in the developing world and promoting state sovereignty.

- Maoist policy emphasized “intermediate zones,” areas that were dissatisfied with or concerned about American control.

- Beijing developed a vision of an “alternative pole” characterized by independence and opposition to hegemony.

- This diplomatic outreach approach had a vision to promote anti-American rhetoric, socialism, and a global structure for independence under their leadership as the center of the global stage.

- “Mao’s transformation of the CCP into a successful political and military machine represented an alternative model… for those movements of national liberation in semicolonial and colonial countries that were trying to achieve independence in the Southern Hemisphere.”

- Active involvement included investing political capital in the intermediate zones to reinforce China’s relevance.

- In the early 1970s, Beijing shifted from “revolution” towards “development” as the current shifted towards economic development and reform as a tool of resistance.

- The US emphasis on economic and political liberalization threatened to challenge China’s leadership role.

- However, Beijing has combatted this through significant economic investment across the world that creates alternative structures.

- The Gulf has become a critical “intermediate zone” for Beijing because of its rising significance as political and economic leaders in the region and beyond.

- China played a crucial role in the Gulf’s growth due to its growing need for energy and willingness to engage in new projects and trade with regional states.

- Beijing has become so rooted in the region that Gulf states are minimally responsive to US pressures to end cooperation with China.

- This quieter, non-military approach is in line with historic foreign policy as it allows China to create alternatives to the US for states that may encourage gradual detachment and greater independence.

- Increasing direct political engagement may be indicating China’s willingness to become more actively involved, defying Maoist approaches of “soft patronage.”

- However, recent activity indicates that Beijing is still driven more by its anti-hegemonic concern than a desire to act as an alternative to traditional US leadership.

You can read “The Role of the Gulf in the Longue Durée Of China’s Foreign Policy” by Enrico Fardella and Gangzheng She in the Spring 2024 issue of Middle East Policy.

(Banner image: Inat.fr)